How

did this veteran of the Pacific Theater in

World War II become so worked up?

It

is a passion that grew from an adventurous

life.

As

a young singer from just outside Baltimore,

he moved to Florida well before Disney, so he could attend Stetson

University in DeLand. In his words, it was a "natural wonderland"

teeming with unique plants and animals in balance with an environment

so clean he could smell the citrus trees.

He

was into his fourth year at Stetson when he

left, joining the Navy in 1944. He saw action and survived several

close calls.

But

when a wave threw him against a boat, he

suffered nerve damage that he believes caused the tremor that slows him

even today.

Back

in the States, he landed jobs at radio

stations in Annapolis and Washington D.C.

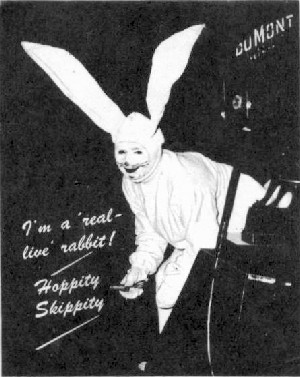

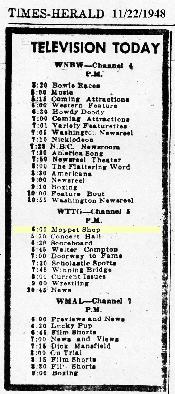

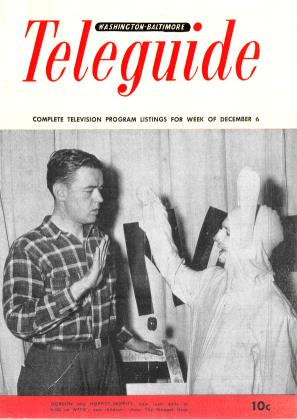

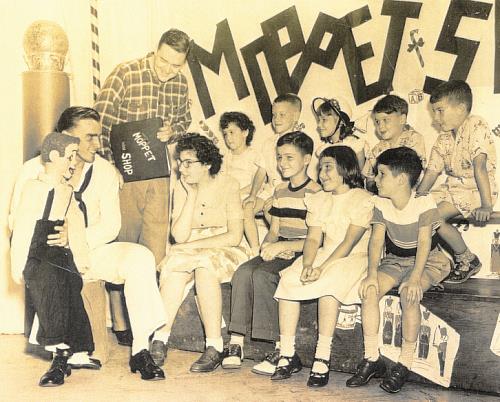

Before

long, he was hired on at WTTG, the first

television station in Washington. He started as a booth announcer,

introducing programs, and became an on-air personality, reading news

and playing the straight man alongside a children's show character

named Hoppity Skippity.

"I

even have people come up to me today and say

they remember the show and were devoted fans," he said. "It was fun to

do."

The

era was a pioneering, fun time, and

Williamson was involved in some groundbreaking moments.

For

instance, he can't remember whether it was

1947 or 1948, but he recalls working as a commentator on the first

broadcast from Capitol Hill, a House Armed Services Committee hearing

involving then-Gen. Dwight David Eisenhower.

Williamson

also played Santa Claus and met such

entertainment giants as Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, Duke

Ellington and Billie Holiday as they visited the station for live,

on-air performances.

Eventually,

he moved into advertising and

executive positions at television stations and ad agencies in

Greensboro, N.C., Charleston, S.C., and Orlando.

But

while television is a sweet spot of memories

for Williamson, it is also a source of sourness.

"I

think it's lost its soul," he said. "It seems

that anything goes and there's so much deception.

"They

can spin something that's not correct into

something the public believes is true."

As

ownership of most television stations has

fallen into the hands of the same seven or eight conglomerates, the

business has lost much of its originality, he said.

He

and wife Natalie Dix, the retired Daytona

Beach News-Journal editorial page editor (who first met Williamson at

Stetson in the 1940s), limit their viewing to mainly news-oriented

programs and Comedy Central's "The Daily Show with Jon Stewart."

Instead,

he spends a lot of time admiring the

mostly wild plants and flowers that provide cover for his home.

"I

believe cutting trees is responsible for

other problems we have today. We bare too much land and it allows the

sun to dry it out and reduces our evaporation."

He's

convinced deforestation has altered the

state's climate, raising temperatures. "We seldom hit 90," in the

1940s, he said.

Politically,

he had embraced the conservative

message of Barry Goldwater in the 1960s, but he returned to Florida in

1970 and his concern for the environment grew. He switched to the

Democratic Party in the late 1980s.

Williamson

volunteered for environmentalist Reid

Hughes, a Democratic candidate for Congress in 1982 and 1990. Hughes

said his background in television and radio was invaluable to his

campaigns, though Hughes lost close races to incumbents both times.

"He

works harder than the rest of us," Hughes

said. "He has been an inspiration to the environmental constituency

with his leadership."

Another

cause Williamson took up was

overpopulation and its societal and environmental effects. For years,

he traveled the state, giving presentations on the problem.

But

the message never seemed to catch on.

"I

think I'm more disillusioned by the human

condition than anything else," he said. "I think I'm frustrated because

in Florida, we're continuing to do the things that are not good for us.

"I'm

a pessimist, I guess, and I hate to be a

pessimist. I look across the world and I see people starving and I see

genocide and what's going on in Iraq and Palestine and I'm frustrated

that I can't do anything about it."

Williamson

insists his anger has little or

nothing to do with his family life. He was married once, and divorced,

and has not spoken to his adopted son for many years.

He

stays busy. He travels and continues

strategizing with groups such as the Volusia-Flagler Environmental

Action Council. He talks about finishing his life story.

In

quiet moments at home, he admires the lizards

he claims drink from a manmade pond he had dug in his backyard in Holly

Hill, an otherwise largely urban city. He watches the koi.

He

notices an air potato vine growing on one of

his palm trees, and thinks to himself, "Gee, I've got to get that taken

care of."

He

tries to steady that tremor.

Copyright

© 2004

News-Journal Corporation